ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA SPEAKS

Highlights from the Yale Babylonian Collection

This is the accessible version of the tour designed specifically for users needing extra accessibility features.

Ancient Mesopotamia Speaks. Intro banner

INTRO

SECTION 1: WRITING

SECTION 2: HEROES, GODS AND DEMONS

SECTION 3: DAILY LIFE

SECTION 4: KINGS, CRIMINALS, AND CONSPIRATORS

SECTION 5: SCIENCE AND SCHOLARSHIP

SECTION 6: YALE BABYLONIAN COLLECTION

INTRODUCTION

Exterior of the museum

Ancient Mesopotamia, the “Land between the Rivers,” was the birthplace of writing, urban culture, the state, and many other concepts and institutions that shape our world to this day. Stretching from the Tigris to the Euphrates in what is now Iraq and Syria, Mesopotamia has produced beautiful and intriguing works of art, myths and epics celebrating gods and heroes, treatises on mathematics and medicine, but also thousands of letters by ordinary people, and even the world’s first cookbooks.

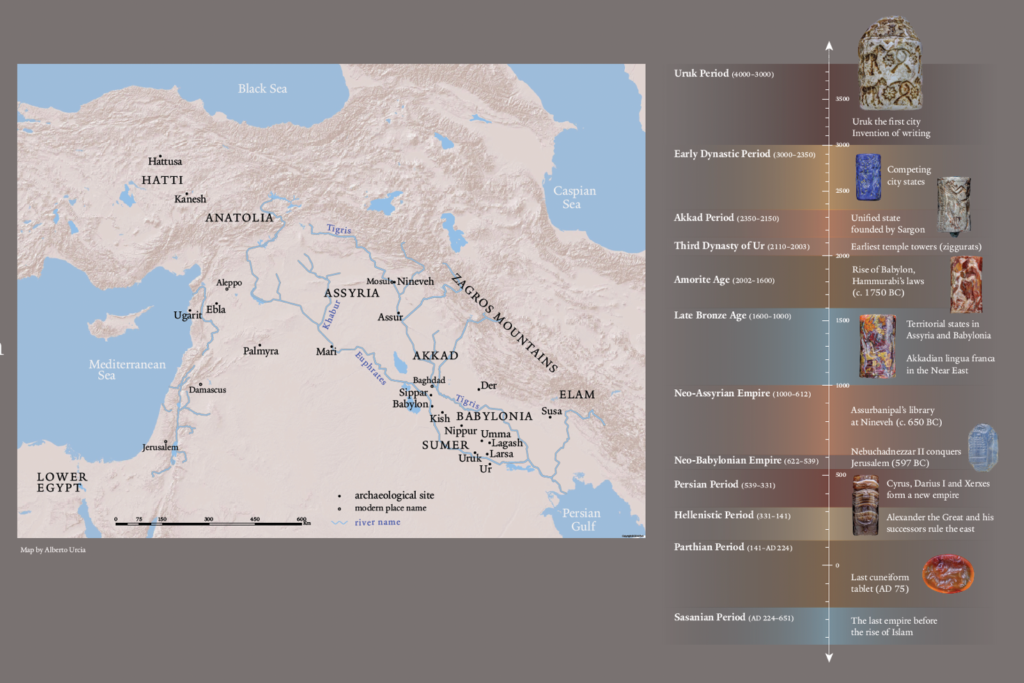

BANNER: Map and timeline

The Euphrates near Anah, 1920, Yale Babylonian Collection Archives

On view here are some one hundred and fifty artifacts, from clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform to intricately carved seals to monumental basreliefs. Almost all are from the Yale Babylonian Collection, founded in 1911 and today one of the major repositories of Mesopotamian artifacts outside Iraq. At a time when Mesopotamian cultural heritage is gravely endangered, the objects on display here seek to give voice to this ancient civilization and allow Mesopotamia to “speak” again, through its texts and imagery.

Map of the Mesopotamia (by Alberto Urcia)

BANNER: Archaeology and Cultural Heritage

Image on left: Scientific excavation in progress at Ur in southern Iraq in 2015.

Image on right: The site of Umma in southern Iraq, pockmarked with hundreds of looters’ pits in 2012.

Archaeological sites and their artifacts, especially in the Middle East, are a nonrenewable cultural heritage in constant danger. Along with development, erosion, and neglect, many Middle Eastern sites have suffered from looting, military activity, and deliberate destruction.

Ancient Mesopotamia Speaks bears witness to what has been lost and seeks to counter attempts by radical forces to silence a sometimes inconvenient past. And yet, admittedly, most objects here are not from scientific excavations. During the Yale Babylonian Collection’s first decades artifacts were commonly bought, with little interest in documenting where they were found. Although this has deprived us of important data, we can still reconstruct the cultural settings of many objects.

BANNER: Credits

The temple tower at Nimrud. 1920. Yale Babylonian Collection Achieve

SPONSORS

The Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History gratefully acknowledges the following for their contributions and support of this exhibition.

Edward P. Bass ’67

Connecticut Humanities

Victoria K. DePalma

The Viscusi Fund of the Department of Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations, Yale University

Hawkinson Conservation and Exhibition Fund

The Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage

Curated by Agnete W. Lassen, Eckart Frahm and Klaus Wagensonner

SECTION 1: WRITING

Writing emerged in southern Mesopotamia in the second half of the fourth millennium BC. At first pictographic, with symbols resembling physical objects, signs would soon become more abstract and develop into the writing system known as cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”), because of its characteristic clusters of triangular impressions left by a reed stylus on damp clay. Cuneiform has roughly one thousand signs that represent both words and syllables. Mostly used to write Sumerian and Akkadian, it was later adapted for other languages.

Cuneiform initially served to record economic texts and word lists. Over time, it was also used to write letters, contracts, royal inscriptions, literary and religious texts, medical treatises, rituals and

incantations, dictionaries, and much more. Lost and forgotten since the first centuries AD, these texts speak to us again today thanks to the dedicated scholars who deciphered cuneiform in the nineteenth century.

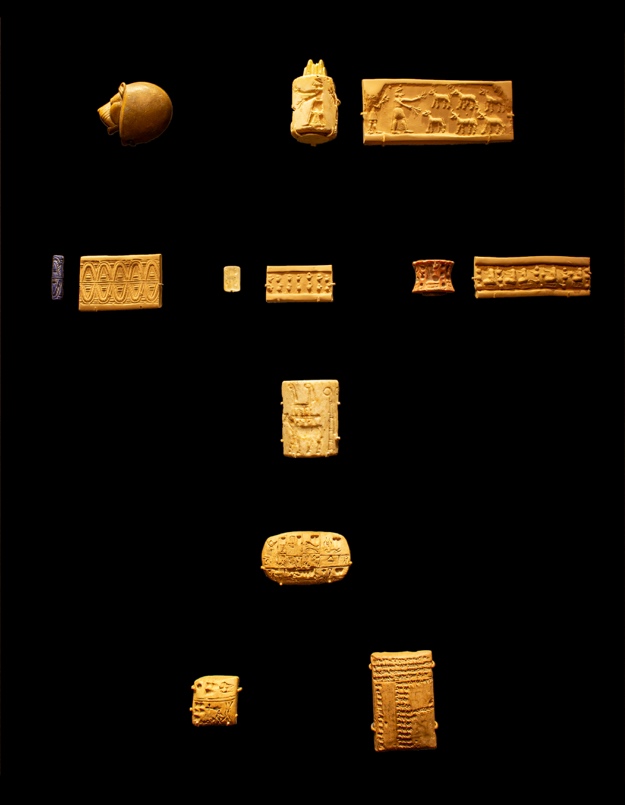

Panel: Early Information Technology

Stamp and cylinder seals were an early form of information technology that from the seventh millennium bc onward marked ownership or association. In the fourth millennium bc, they were impressed on bullae, hollow clay balls that accompanied goods and contained small clay tokens symbolizing commodities and their quantities. The first writing borrowed symbols from these tokens, but integrated them into a much more advanced system. Over time, sign shapes changed considerably.

Object 1: Stamp Seal in the Form of a Lion Head

Limestone

Uruk period (c. 4000–3000 bc)

Possibly from Susa

YPM BC 036918

NCBS 21

Object 2: Cylinder Seal with Priest-king Feeding a Herd

Marble

Above is a digitally rolled out image of this seal

Late Uruk period (c. 3500–3000 bc)

YPM BC 005552

NBC 2579

Object 3: Piedmont Style Cylinder Seal

Lapis lazuli

With rolled out impression on polymer

Late Uruk period (c. 3500–3000 bc)

YPM BC 038015

NBC 12151

Object 4: Cylinder Seal with Vessels

Rock crystal

With rolled out impression on polymer

Late Uruk period (c. 3500–3000 bc)

YPM BC 038016

NBC 12141

Object 5: Cylinder Seal Showing Women Engaged in Pottery-making

Red marble

With rolled out impression on polymer

Late Uruk period (c. 3500–3000 bc)

YPM BC 036926

NCBS 29

Object 6: Cylinder Seal Fragment Showing a Bull Carrying an Image of Inana

Marble

With rolled out impression on polymer

Late Uruk period (c. 3500–3000 bc)

YPM BC 036919

NCBS 22

Object 7: An Early Account of Slaves

Clay

Uruk III period (c. 3300-3000 bc)

Possibly from Larsa

YPM BC 008902

NBC 5921

Object 8: An Early Account of Small Cattle

Clay

Uruk III period (c. 3300-3000 bc)

Southern Babylonia

YPM BC 021120

YBC 7056

Object 9: A Late Account of Small Cattle

Clay

Persian period, January 13, 526 bc

Uruk

YPM BC 018036

YBC 3971

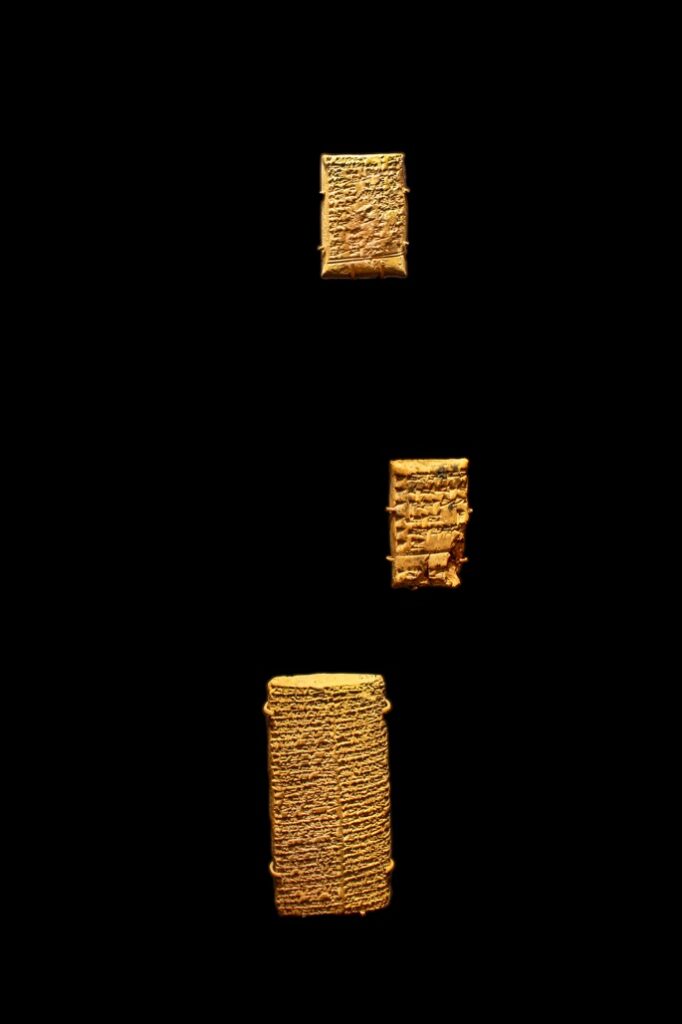

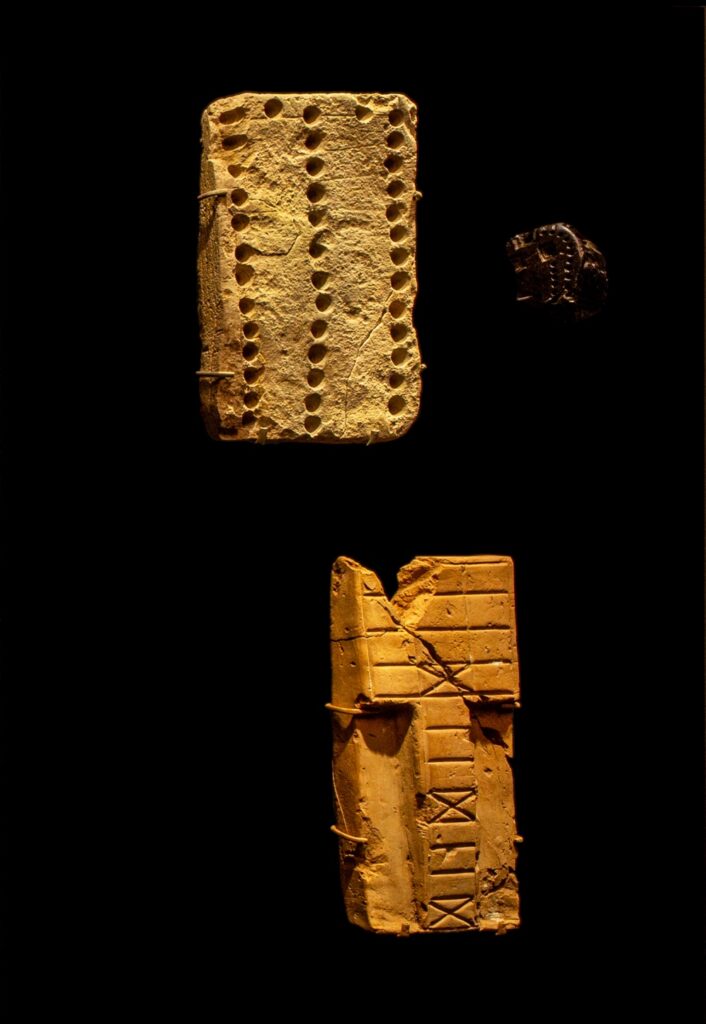

Panel: Materials and shapes

Clay was the main writing medium, but cuneiform was also written on stone and metal. It was used on objects of all shapes and sizes, from minute to monumental, from rectangular to round, and on prisms, cylinders, cones, and triangular tags.

Object 1: Stone Foundation Tablet of Ur-Nammu

Steatite

Ur III period, reign of Ur-Nammu (c. 2110–2093 BC)

Possibly from Uruk

YPM BC 002577

MLC 2629

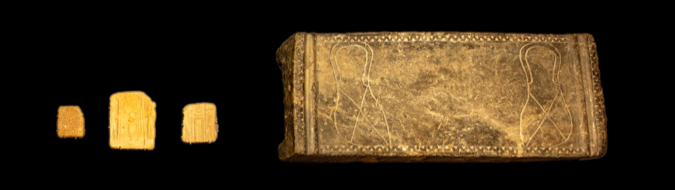

Object 2: Two Foundation Tablets

Gold and silver

Neo-Assyrian period, reign of Assurnasirpal II

(883–859 BC)

Apqu (Tell Abu Marya)

YPM BC 016991, YPM BC 016992

YBC 2398, YBC 2399

Object 3: Foundation Figurine Dedicated to Ninmarki

Cast bronze

Second Dynasty of Lagash (c. 2200–2100 BC),

reign of Ur-Ningirsu I

Possibly from Lagash

YPM BC 016871

YBC 2248

Object 4: Brick Stamp

Clay

Old Akkadian period, reign of Shar-kali-sharri

(c. 2217–2192 BC)

YPM BC 016914

YBC 2310

Object 5: Eyestone Dedicated to Ninlil

Agate

Old Babylonian period, reign of Lipit-Eshtar

(c. 1870–1860 BC)

Possibly from Nippur

YPM BC 016969

YBC 2374

Object 6: Cylinder Seal with a Prayer to Marduk

Milky agate

With rolled out impression on polymer

Kassite period (c. 1590–1155 BC)

YPM BC 006190

NBC 3217

Object 7: Large Cylinder with a Name List

Clay

Probably Ur III period (c. 2100–2000 BC)

YPM BC 016757

YBC 2124

Object 8: A Duplicate of the Name List Written in Minute Script

Clay

Probably Ur III period (c. 2100–2000 BC)

Nippur

YPM BC 014052

NBC 11202

Panel: Organizing Cuneiform Characters

The number of cuneiform signs that were actually in use differed from period to period and from genre to genre. This tablet is a full inventory of signs used by scholars of the early second millennium BC for Sumerian literary texts. The list is ordered by the shape of the signs.

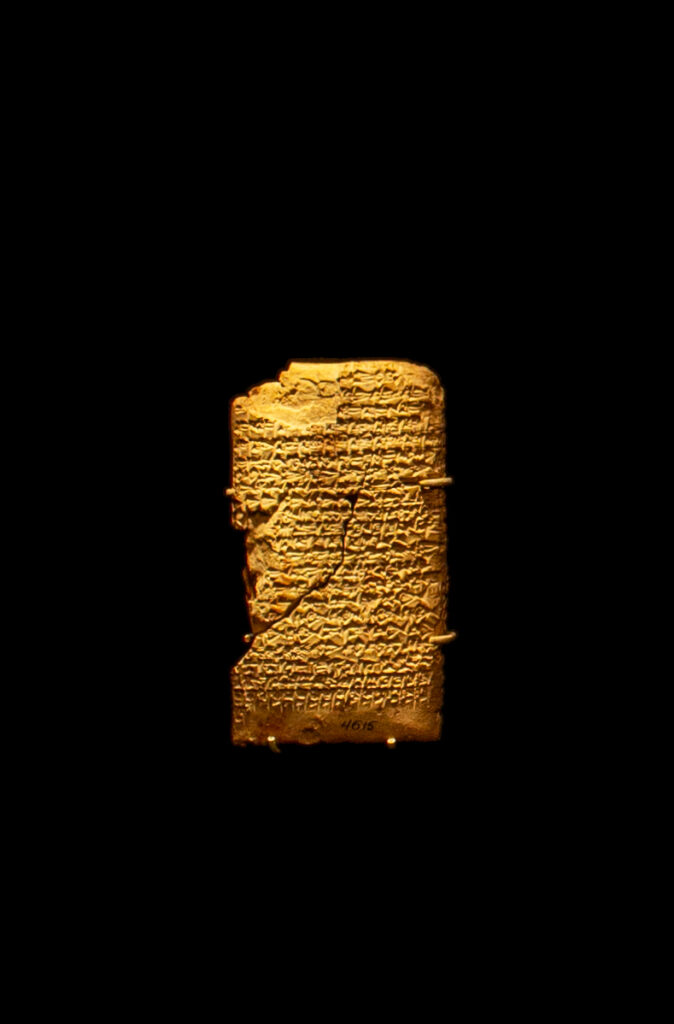

A Handbook of Signs

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Possibly from Larsa

YPM BC 018680

YBC 4615

Panel: Rediscovery and Decipherment

The latest cuneiform text we have was written in AD 75. With exploration of ancient ruins from the eighteenth century onward, cuneiform inscriptions reemerged. Old Persian texts from Persepolis were the first deciphered. Major excavations at Nineveh and Nimrud by Austen Henry Layard and others led, by 1857, to the decoding of Babylonian and Assyrian cuneiform.

At the Ruins of Nimrud, 1920 Yale Babylonian Collection Archives

Missing image

Object: Sketch of a Winged Colossus

Ink on paper

Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894)

AD 1857

England

YPM BC 038106

YBC 10192

Layard, the first to excavate Nineveh and Nimrud, made this sketch during one of his many stays with his cousin Lady Charlotte at her home Canford Manor in Dorset, England. The drawing may show one of the large stone sculptures of human-headed winged bulls and lions on display there.

Object: Vase with Inscription in Five Scripts

Alabaster

Achaemenid period, reign of Xerxes (485–464 BC)

YPM BC 016756

YBC 2123

The name and titles of Xerxes are inscribed here in Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian cuneiform, and in Egyptian hieroglyphs. A fifth inscription in Demotic, a late Egyptian script, gives the capacity of the vase.

Object: Restored Interior of an Assyrian Palace

Printed cotton canvas with overpainting

Artist unknown

AD 1852

England

Anonymous loan

This was one of a series of illustrations commissioned by the British Working Men’s Educational Union for use in public lectures about Assyrian sites and arti acts excavated by Austen Henry Layard.

SECTION 2: HEROES, GODS AND DEMONS

For the people of ancient Mesopotamia the world was full of supernatural beings. Gods and monsters fought epic battles that decided the rise and fall of cities, states, and dynasties. The supernatural and human worlds were closely connected and the divine realm directly influenced human existence.

The Mesopotamians believed in many gods, smaller ones who were personal deities and the greater gods of myths and legends. Heroes, such as the famed Gilgamesh, boasted super-human strength and partly divine ancestry. Evil demons inflicted illness, death, and misfortune, whereas benevolent ones provided support against such calamities.

Panel: Gilgamesh

Mesopotamia’s most famous heroic king, Gilgamesh, is the protagonist of many Sumerian and Akkadian literary works. His journey to slay the monstrous Humbaba (earlier Huwawa) and his quest for eternal life fascinated ancient Mesopotamians and also resonate with audiences today. The account of the Deluge in the Gilgamesh epic intriguingly parallels the biblical story of Noah and the Flood.

Object 1: Humbaba Mask

Terracotta

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 007441

NBC 4465

Object 2: “Gilgamesh and the Cedar Forest”

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Probably from Larsa

YPM BC 016806

YBC 2178

Object 3: Humbaba Mask

Terracotta

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 038065

YBC 10066

Object 4: Macehead Dedicated to Gilgamesh

Limestone

Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2540–2350 BC)

Possibly from Girsu

YPM BC 016772

YBC 2144

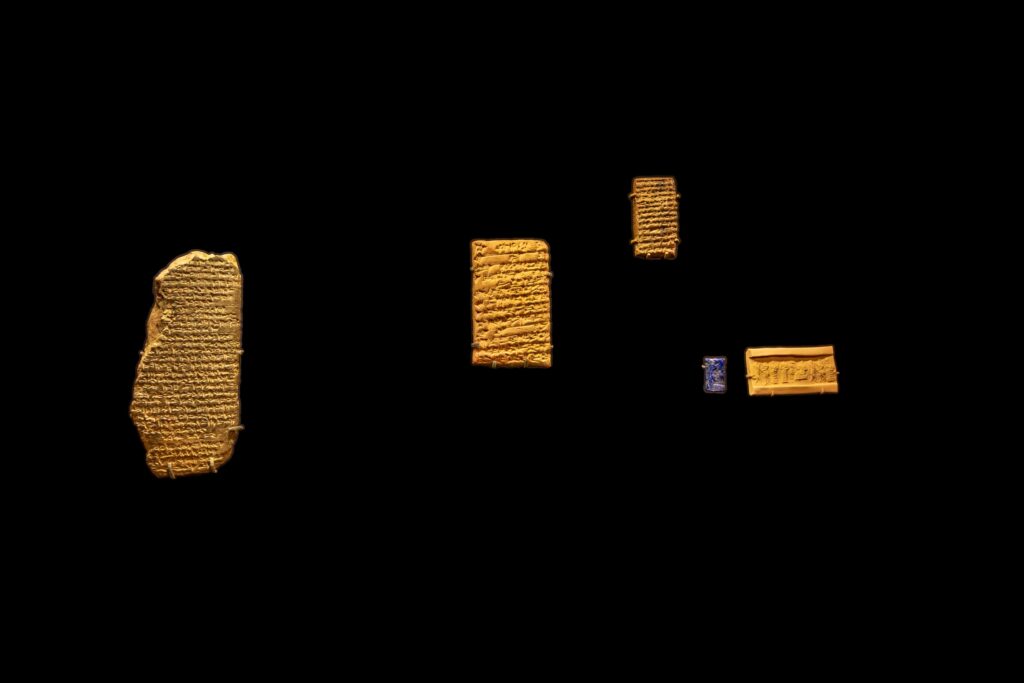

Panel: Ishtar, Goddess of Love and War

The Sumerian Inana, Ishtar in Akkadian, represented love and war, ascended to heaven and descended to the netherworld, and embodied transvestism and a topsy-turvy world. She owed her position not to marriage, but to her own qualities. “The Exaltation of Inana,” an early text celebrating the goddess, is by the princess Enhedu-ana (twenty-third century BC), the first recorded author in human history.

Object 1: “The Exaltation of Inana,” Part I

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Probably from Larsa

YPM BC 018721

YBC 4656

Object 2: “The Exaltation of Inana,” Part II

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Probably from Larsa

YPM BC 021234

YBC 7169

Object 3: “The Exaltation of Inana,” Part III

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Probably from Larsa

YPM BC 021231

YBC 7167

Object 4: A Love Song from Inana for Dumuzi

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 013883

NBC 10923

Object 5: Cylinder Seal Showing Divine Ishtar

Chalcedony

Above is a digitally rolled out image of this seal with rolled out impression on polymer

Neo-Assyrian period (934–612 BC)

YPM BC 038108 NBC 12332

Object 6: Cylinder Seals Showing Ishtar as a Warrior and the Sun-god

Hematite

Below is a digitally rolled out image of this seal with rolled out impression on polymer

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 037115 NCBS 218

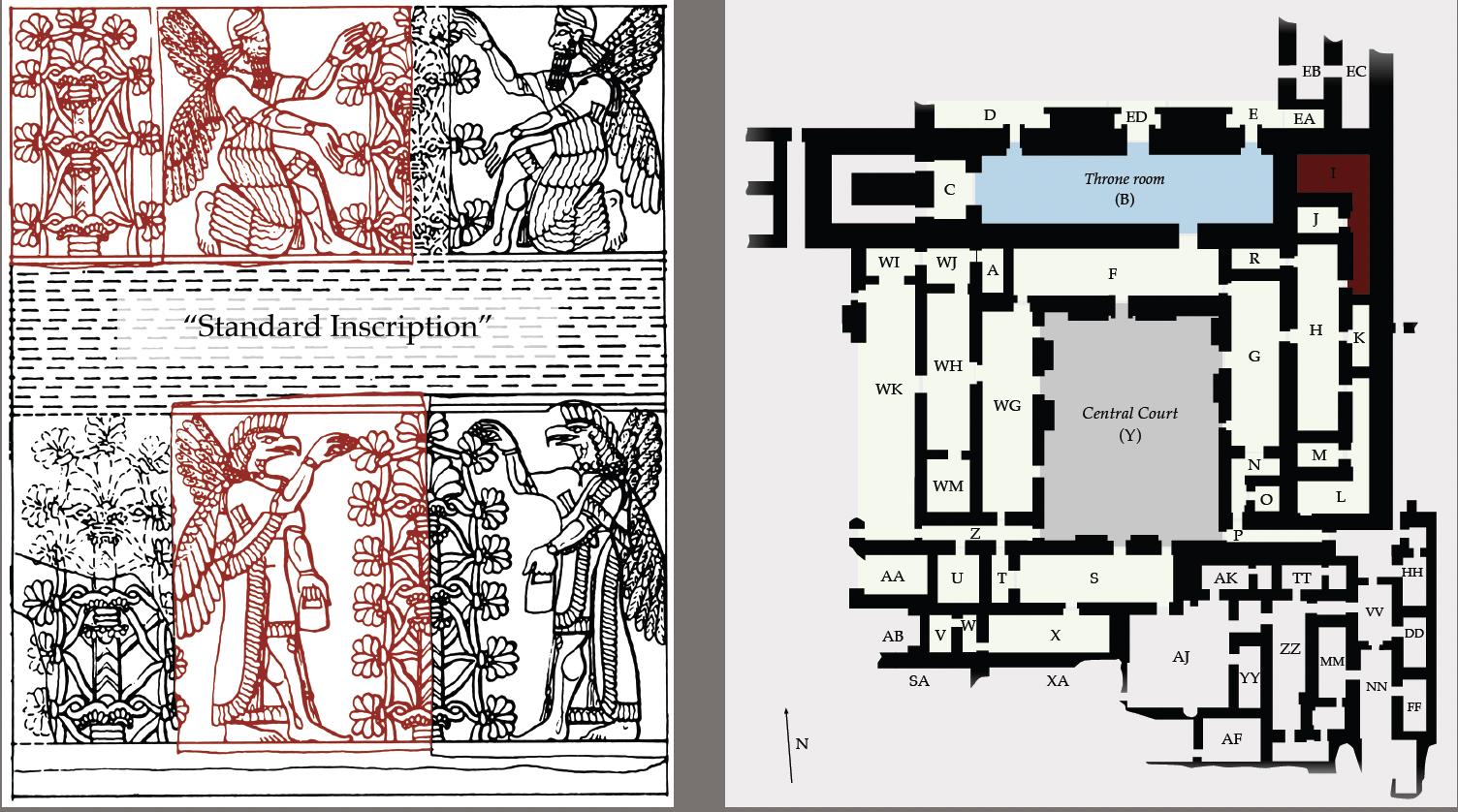

Panel: Supernatural Beings on Assyrian Reliefs

Assyrian palaces were adorned with monumental stone slabs carved with religious motifs and historical scenes commemorating military achievements. Popular under the ninth century BC king Assurnasirpal II were scenes of protective spirits and a “sacred tree.” The two relief fragments here come from a palace room used for purification and cleansing rituals.

Carved Relief Showing Standing Eagle-headed Genius Facing a “Sacred Tree”

Alabaster

Neo-Assyrian period, reign of Assurnasirpal II

(883–859 BC)

Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room I

Yale University Art Gallery

YUAG 1854.3

Carved Relief Showing Kneeling Human-headed Genius Facing a “Sacred Tree”

Alabaster

Neo-Assyrian period, reign of Assurnasirpal II

(883–859 BC)

Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room I

Yale University Art Gallery

YUAG 1854.4, YUAG 1854.5

Left

Slab from Room I with the two relief fragments on display marked in red.

Right

Layout of the North-West Palace with Room I marked in red.

Panel: Monsters, Demons, and Genies

Mesopotamian monsters and demons usually had no families and played no role in the temple cult. Half human and half animal, they inhabited a space between the divine and the human. Monsters were associated with gods and heroes, demons and benevolent genies interacted mainly with humans and the natural world.

Object 1: Head of the Demon Pazuzu, Protector against Evil

Clay

Probably Late Babylonian period (second half of the first millennium BC)

Nippur

YPM BC 016825

YBC 2197

Object 2: Cylinder Seal Showing the Demons Pazuzu, Lulal, and Ugallu

Blue chalcedony

Above is a digitally rolled out image of this seal with rolled out impression on polymer

Neo-Babylonian period (first half of the first millennium BC)

YPM BC 026360

YBC 12601

Object 3: Plaque Depicting a “Hero with Six Curls”

Clay

Middle Assyrian period (c. 1400–1000 BC) or Neo-Assyrian

period (c. 934–612 BC)

Possibly Assur

YPM BC 038025

YBC 10086

Object 4: Plaque with a “Fish-apkallu,”a Protective Spirit

Clay

Neo-Assyrian period (934–612 BC)

YPM BC 038026

YBC 10168

Object 5: Incantations against Evil Demons

Clay

Late Babylonian period (second half of the first millennium BC)

YPM BC 004279

NBC 1307

Object 6: Cylinder Seal Showing Battles between Humans and Demons

Hematite

With rolled out impression on polymer

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 037054

NCBS 157

Object 7: Monsters Fighting

Carnelian

With rolled out impression on polymer

Neo-Babylonian period (first half of the first millennium BC)

YPM BC 023720

YBC 9668

Object 8: An Incantation against the Child-snatching Demoness Lamashtu

Clay

Old Assyrian period (c. 2000–1700 BC)

Central Anatolia

YPM BC 006647

NBC 3672

Object 9: An Amulet against Lamashtu

Marble

Second millennium

YPM BC 016821

YBC 2193

Object 10: An Amulet against Lamashtu

Alabaster

Late second millennium

Allegedly from Uruk

YPM BC 005502

NBC 2529

Object 11: An Amulet against Lamashtu

Obsidian

Late second or early first millennium

YPM BC 011147

NBC 8151

Panel: The Mesopotamian Pantheon

Mesopotamian religion was polytheistic with countless divine beings. Religious texts mention many gods organized in families and supplied with their own personnel. Some gods were patrons of cities. The moon god Sin resided over Ur and the goddess of love and war, Ishtar, over Uruk.

Object: A List of Thousands of Gods

Clay

Middle Assyrian period (c. 1400-1000 BC)

Assur

YPM BC 016994

YBC 2401

Panel: Gods Visible and Invisible

Deities were often worshipped in Mesopotamia in the form of human-shaped statues that wore clothes and jewelry. Sometimes divine symbols and “emblems of emptiness” replaced such anthropomorphic representations, indicating a belief in the invisibility of certain aspects of the world of the gods.

From left to right

Object: Letter Reporting a Theft in a Temple of the God Assur

Clay

Old Assyrian Period (c. 2000–1700 BC)

Kanesh, Anatolia

YPM BC 009599

NBC 6615

Object: Plaque with Temple Façade and Seated Deity

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 038109

YBC 10035

Object: Plaque with Temple Façade

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 016771

YBC 2143

Object: Ornamental Footrest for a Deity

Chlorite

Late third millennium

Possibly from eastern Iran

YPM BC 016999

YBC 2407

SECTION 3: DAILY LIFE

The people of ancient Mesopotamia fell in love and married, enjoyed music, games, and cooking, and interacted with animals and pets. Like us today, they also had to cope with family conflicts, childlessness, adultery, divorce, and death.

People lived their lives as members of small family households, typically a father and a mother, children, and sometimes grandparents. Slaves owned by well-off families would also belong to the household.

Men occupied different professions, from farmer to seal-cutter. Women were legally entitled to own property, enter contracts, and engage in business, but many tended to stay at home. Others worked in the fields, or were tavern keepers, midwives, or priestesses.

Panel: Love

Mesopotamian men and women often sought to secure another’s affections through magic and incantations. Terracotta plaques celebrate erotic attraction with graphic depictions of lovemaking. Some show a man approaching a woman bent at the waist and sipping beer through a drinking tube. The exact function of the plaques is debated.

Object: List of Love Incantations

Clay

Late Babylonian period, late fourth century

Uruk

YPM BC 001857

MLC 1859

Top right

Object: Mold with Erotic Scene

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 007452

NBC 4476

Bottom right

Object: Plaque with Erotic Scene

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 016962

YBC 2367

Panel: Marriage

Marriage between men and women was as fundamental a social institution in ancient Mesopotamia as it is today. A marriage contract stipulated the conditions of the union. Most were monogamous, but if a wife remained childless or the partners had a permanent long-distance relationship, a man could take a second wife.

Left to right

Object: Legal Document for the Marriage between Nabu-ahu-usur and Tala-Uruk

Clay

Neo-Babylonian period, 512

Uruk

YPM BC 017797

YBC 3732

Object: Plaque Showing an Embracing Couple

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 038111

YBC 10025

Object: Letter from Lamassi to Her Husband Pushu-ken

Clay

Old Assyrian period (c. 2000–1700 BC)

Kanesh, Anatolia

YPM BC 006791

NBC 3816

Panel: Children

Married couples were eager to have children, to care for them in old age and provide funerary offerings after death. Often sons took up the profession of their fathers. With no male heir, a man could take a second wife or the couple could adopt. Figurines and texts relate caring relationships between generations.

Object 1: Figurine of a Mother and Her Child

Clay

Hellenistic period (331–141 BC) or

Parthian period (141 BC – AD 224)

YPM BC 038110

YBC 10059

Object 2: Figurine of a Mother and Her Child

Clay

Neo-Babylonian period (first half of the first millennium BC)

YPM BC 016846

YBC 2223

Object 3: Figurine of a Mother and Her Child

Clay

Hellenistic period (331–141 BC) or

Parthian period (141 BC – AD 224)

YPM BC 007427

NBC 4451

Object 4: Ritual to Quiet a Child

Clay

Late Babylonian period (second half of the first millennium BC)

Possibly from Nippur

YPM BC 009132

NBC 6151

Object 5: Adoption Contract

Clay

Old Babylonian period, c. 1743

Possibly from Ur

YPM BC 004244

NBC 1272

Object 6: A Letter to Mom

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Possibly from Larsa

YPM BC 008268

NBC 5289

Panel: Adultery, Divorce, and Death

Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Wedded couples in Mesopotamia would experience major troubles when one of the partners engaged in adultery. There might be a divorce. And when people died, the division of their estates did not always prove easy.

Object: Riddle about an Adulterer

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 019893

YBC 5828

Object: Legal Statement Recording a Divorce

Clay

Old Babylonian period, probably eighteenth century

Possibly from Larsa

YPM BC 036445

NCBT 1900

Object: Legal Document about Brothers Sharing an Inheritance

Clay

Old Babylonian period, c. 1816–1794

Possibly from Isin

YPM BC 008321

NBC 5341

Panel: Music and Entertainment

Like today, music, sports, and games were part of everyday life. Some of these activities had ritual significance and some were just for fun. We have musical scores from the second millennium BC, but they are difficult to interpret. A few instruments and board games have been preserved in the archaeological record.

Object 1: Pie Crust Rattle

Clay

Third or early second millennium

YPM BC 023979

YBC 10043

Object 2: Nude Male Figurine Holding a Tambourine

Clay

Hellenistic period (331–141 BC) or

Parthian period (141 BC – AD 224)

YPM BC 016862

YBC 2239

Object 3: Nude Female Figurine Holding a Tambourine at Her Chest

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 023976

YBC 10001

Object 4: Dwarf Playing a Harp

Clay

Hellenistic period (331–141 BC) or

Parthian period (141 BC – AD 224)

YPM BC 016852

YBC 2229

Object 5: Female Musician Playing a Harp

Clay

Hellenistic period (331–141 BC) or

Parthian period (141 BC – AD 224)

YPM BC 016826

YBC 2198

Object 6: Text Exploring the Religious Dimensions of the Strings of the Lyre

Clay

Late Babylonian period

(second half of the first millennium BC)

Possibly from Uruk

YPM BC 025175

YBC 11381

The tablet lists the words of several short prayers, each related to a particular string of the lyre. The prayers may have been chanted to the pitch of the respective string.

Object 7: A Game with Forty-one Holes

Clay

Probably Old Babylonian period

(c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 038044

YBC 10089

Object 8: The Game of Fifty-eight Holes

Serpentine

Probably Old Babylonian period

(c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 017030

YBC 2439

Object 9: The Game of Twenty Squares

Clay

Probably Old Babylonian period

(c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 038112

YBC 2396

Panel: Cooking

Many of our most important food staples originated in the Near East, including barley and wheat, and animals such as cows, sheep, and pigs. The world’s oldest written recipes, recorded in southern Mesopotamia around 1700 BC, are instructions for stews and pies. They reveal a sophisticated kitchen that used many different cooking techniques.

Object: A Babylonian Cookbook

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Possibly from Larsa

YPM BC 018709

YBC 4644

Objects: Two Cylinder Seals Showing Banquet Scenes

Rock crystal

Green calcite

With rolled out impression on polymer and a digitally

rolled out image of each seal

Early Dynastic III period (2600–2350 BC)

YPM BC 023974

YBC 9991

YPM BC 008968

NBC 5987

(Recipe no. 9) Pashrutu-dish

Meat is not used. You prepare water. You add fat. (You add) kurrat, cilantro, salt as desired, leek, garlic. You pound up dried sourdough, you sift (it) and you scatter (it) over the pot be ore removing it.

(Recipe no. 12) Lamb Stew

Meat is used. You prepare water. You add fat. You add fine-grained salt, dried barley cakes, onion, Persian shallot, and milk. You [crush] (and add)

leek and garlic.

(Recipe no. 16) Elamite Broth

Meat is not used. You prepare water. You add fat. Dill, kurrat, cilantro, leek, and garlic bound with blood, a corresponding amount of sour milk, and (more) garlic. The (original) name of this dish is Zukanda.

(Recipe no. 17) Wild-pigeon Broth

You split up the wild pigeon; (other) meat is (also) used. You prepare water. You add fat. Fine-grained salt, dried barley cakes, onion, Persian shallot, leek, and garlic: you soak (these) herbs of yours in milk, and (the dish) is ready to serve.

(Recipe no. 22) Tuh’u-dish

Leg meat is used. You prepare the water. You add fat. You sear. You add salt, beer, onion, arugula, cilantro, Persian shallot, cumin, and red beet, and you crush leek and garlic. You sprinkle coriander from storage on top. You add kurrat and fresh cilantro.

Panel: Animals and Pets

Animals were ever-present in Mesopotamian daily life: as guardians and pets, as a source of meat, dairy products, and wool, or as dangerous predators and pests. The behavior of animals and the sounds they made could be interpreted as auspicious or inauspicious signs. Animal bites and stings required treatment.

Top to bottom

Object: A Letter Order Regarding the Feeding of Cats

Clay

Neo-Babylonian period, mid sixth century

Uruk

YPM BC 025161

YBC 11367

Object: Magic Spells against Worms, Snakes, and Scorpions

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 018681

YBC 4616

Object: Rituals against Ill-omened Animals in the House

Clay

Late Babylonian period (second half of the first millennium BC)

YPM BC 023872

YBC 9873

Panel: Animals in Art

Animal-shaped plaques and figurines were common. Some represent dogs, the earliest domesticated animal. Used as guardians and hunting companions, they are usually shown wearing collars. Stone weights were often shaped like a duck with its head resting on its back. They ranged from less than a tenth of an ounce (2 grams) to 12 pounds (5.5 kilograms).

Left to right

Object: Plaque Showing a Snarling Dog

Clay

Neo-Assyrian period (934–612 BC)

YPM BC 038113

NBC 12112

Object: Hedgehog Figurine

Clay

Period unknown

YPM BC 038116

YBC 10072

Object: Head of a Bull with Greek Inscription

Clay

Hellenistic period (331–141 BC) or later

YPM BC 038115

YBC 10090

Object: Piglets and Mother Pig

Clay

Period unknown

YPM BC 031220

RBC 926

Object: A Monkey with Two Flutes

Clay

Possibly Hellenistic period (331–141 BC)

Probably Babylon

YPM BC 016854

YBC 2231

Objects on Pedestal: A Group of Duck Weights

Hematite, agate, limestone, and chalcedony weighing from 0.07 ounces (2 grams) to 12 pounds (5.5 kilograms)

Late third to late first millennium

YPM BC 037779, YPM BC 032059,

YPM BC 038125, YPM BC 023972,

YPM BC 038126, YPM BC 012512,

YPM BC 009015, YPM BC 016883,

YPM BC 016815

NCBS 882, RBC 1766, YBC 9983, NBC 9519,

NBC 6034, YBC 2262, YBC 2187

Panel: Assurbanipal Banqueting with His Queen

Object: Bas-relief from the North Palace at Nineveh

Plaster cast

Early twentieth century

YPM BC 038054

Original in the British Museum

BM 124920

This well-known bas-relief shows the Assyrian king Assurbanipal (668–631 BC) banqueting with his wife Libbali-sharrat beneath a vine in a garden at Nineveh. The scene includes several remarkable details.

Detail of the Assyrian Queen:

Libbali-sharrat, shown here wearing a mural crown, studied the scribal arts like her husband Assurbanipal.

Detail of the Necklace:

Possibly Egyptian, the necklace slung over the royal couch may be a protective charm.

Detail of the Musicians:

The royal couple is entertained by several musicians, one playing a large harp.

Detail of the Head in the Tree:

The Elamite king Teumman had once threatened the Assyrians, “I shall not [sleep(?)] until I have come and dined in the center of Nineveh.” In the end, it was Assurbanipal who dined there, with Teumman’s head (recognizable by its receding hairline) hanging from a nearby tree.

Detail of Assurbanipal’s Head:

The image of the Assyrian king was deliberately mutilated when the Medes and Babylonians conquered Nineveh in 612 BC.

SECTION 4: KINGS, CRIMINALS, AND CONSPIRATORS

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia gave birth to the earliest complex states in history.

Both civilizations emerged along the shores of major rivers, which enabled the establishment of central governments headed by kings. These monarchs wielded enormous power. They waged war against other states, fortified their borders and cities with walls, engaged in diplomacy, built temples, and produced the earliest collections of laws known from anywhere in the world.

Yet they were never able to completely eliminate criminal behavior, corruption, and subversion. Mesopotamian legal documents and letters show that people committed all sorts of crimes, from murder to theft to smuggling. Mesopotamians also criticized and ridiculed their rulers, and occasionally engaged in acts of rebellion against them.

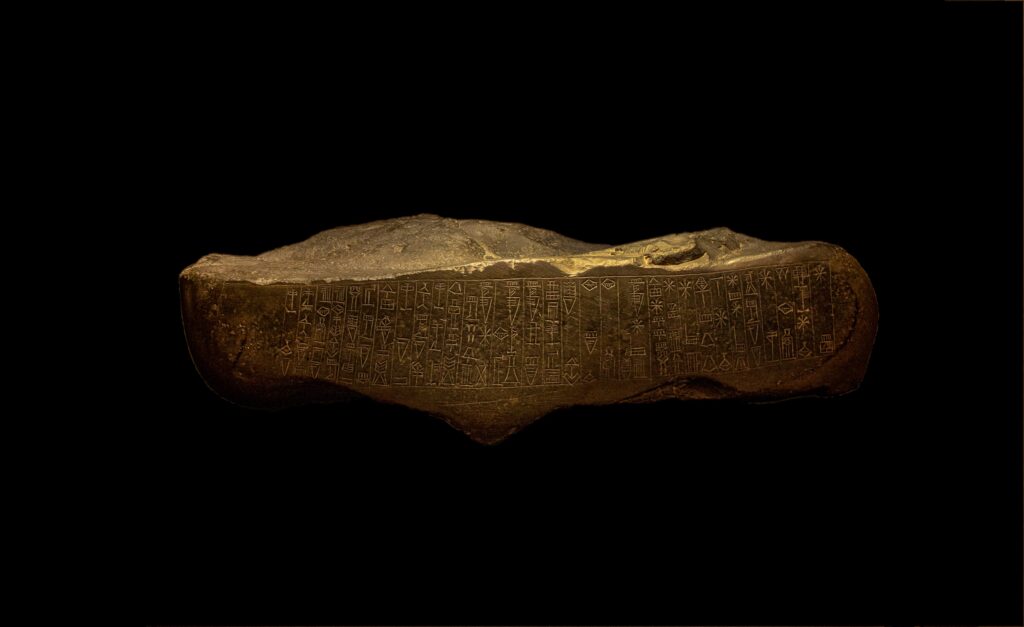

Panel: Fighting for Land and Resources

For long stretches of its history, Mesopotamia was divided into several independent states. These often waged war as territory needed to be protected against outside forces and access to water and other resources had to be secured. The century-long conflict between the neighboring city states of Umma and Lagash is particularly well documented.

Object: Royal Inscription Describing the Umma-Lagash Border Conflict

Clay

Early Dynastic IIIb period, reign of Enmetena of Lagash (c. 2403–2375 BC)

Girsu

YPM BC 005474

NBC 2501

Panel: Building a Wall

In the mid twenty-first century BC, King Shu-Suen of Ur built a wall along his northern border to keep out the semi-nomadic Amorites known as Tidnum. They broke through eventually, but instead of establishing a barbarian regime as feared, the newcomers adapted to Mesopotamian civilization, inaugurating one of the most fruitful eras in Mesopotamian history.

Above left

Object: Tag with a Shu-Suen Year-name Related to the Tidnum Wall

Clay

Ur III period, twenty-ninth day of the second month, c. 2031

Umma

YPM BC 002256

MLC 2309

Above right

Object: Letters from Shu-Suen’s Correspondence about the Tidnum Wall

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Southern Babylonia

YPM BC 021213

YBC 7149

Object on pedestal: Door Socket with Inscription Mentioning the Tidnum Wall

Diorite

Ur III period, reign of Shu-Suen (2035–2027 BC)

Umma

YPM BC 016763

YBC 2130

Panel: Law, Crime, and Punishment

Several rulers from the mid third millennium BC onward—including Hammurabi o Babylon—created collections of laws. Even though they are never directly quoted in legal documents, these collections set the stage for a lawful life. Still, crimes and other violations o the social order continued, as many texts show.

Object 1: Sumerian Laws

Clay

Old Babylonian period

(c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 016805

YBC 2177

Object 2: A Tablet Inscribed with Hammurabi’s

Laws

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 020582

YBC 6516

Object 3: Assyrian Palace Edicts concerning

Royal Women

Clay

Middle Assyrian period, reign o Tiglath-pileser I (1114–1076 BC)

Assur

YPM BC 021212

YBC 7148

Objects 4 and 5: Fragments of Hittite Laws

Clay

Hittite New Kingdom period (c. 1430–1180 BC)

Possibly from Hattusha, Anatolia

YPM BC 014649, YPM BC 014662

NBC 11803, NBC 11816

Object 6: Judicial Document about a Prison

Break

Clay

Persian period, January 529

Uruk

YPM BC 021009

YBC 6943

Object 7: Letter from an Old Assyrian Smuggler

Clay

Old Assyrian period (c. 2000-1700 BC)

Kanesh, Anatolia

YPM BC 004658

NBC 1685

Object 8: Cylinder Seal Showing the Sun-god, the Protector of Justice

Serpentine

With rolled out impression on polymer

Old Akkadian period (c. 2350–2150 BC)

YPM BC 037969

NBC 12229

Panel: Corresponding with Kings

Letters are among the most revealing texts that have survived from the ancient Near East. Royal letters are often about international politics, questions of prestige, and the exchange of precious goods and skilled experts. Letters to kings from officials can be fawning, but illustrate well the challenges of running the affairs of state.

Left to right

Object: Letter from Ramesses II to the Hittite King Hattushili III

Clay

Mid thirteenth century

Hattusha, Anatolia

YPM BC 006909

NBC 3934

Object: Letter from Nebuchadnezzar II concerning Work Done by the Temple

Clay

Neo-Babylonian period, reign of Nebuchadnezzar II

(605–562 BC)

Uruk

YPM BC 021530

YBC 7464

Object: Letter from King Hammurabi concerning a Land Dispute

Clay

Old Babylonian period, reign of Hammurabi

(1790–1752 BC)

Larsa

YPM BC 023958

YBC 9959

Object: Cylinder Seal with Audience Scene

Lapis lazuli

With rolled out impression on polymer

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 006261

NBC 3288

Panel: Propaganda and Reality

Ancient Near Eastern kings produced thousands of images and inscriptions to depict themselves as “ideal rulers.” Letters and legal documents, however, provide a more realistic picture of the Mesopotamian political landscape: subjects often took a rather grim view of their leaders and occasionally were in open revolt against them.

Left to right

Object: Nebuchadnezzar Praising Himself as a Great Builder

Clay

Neo-Babylonian period, reign o

Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC)

Marad

YPM BC 016866

YBC 2243

Object: Esarhaddon Glorifying His Military Conquests

Clay

Neo-Assyrian period, reign of Esarhaddon

(680–669 BC)

Nineveh

YPM BC 029482

YBC 16224

Object: Cylinder Seal Showing the Ideal King

Chalcedony

With rolled out impression on polymer and a digitally rolled out image of this seal

Persian period (539–331 BC)

YPM BC 038107

YBC 8418

Object: A Case of Lèse-majesté (Treason)

Clay

Persian period, April 526

Uruk

YPM BC 018015

YBC 3950

Object: Treason and Revolt in a Letter to Esarhaddon

Clay

Neo-Assyrian period, reign of Esarhaddon

(probably 671 BC)

Probably from Nineveh

YPM BC 025176

YBC 11382

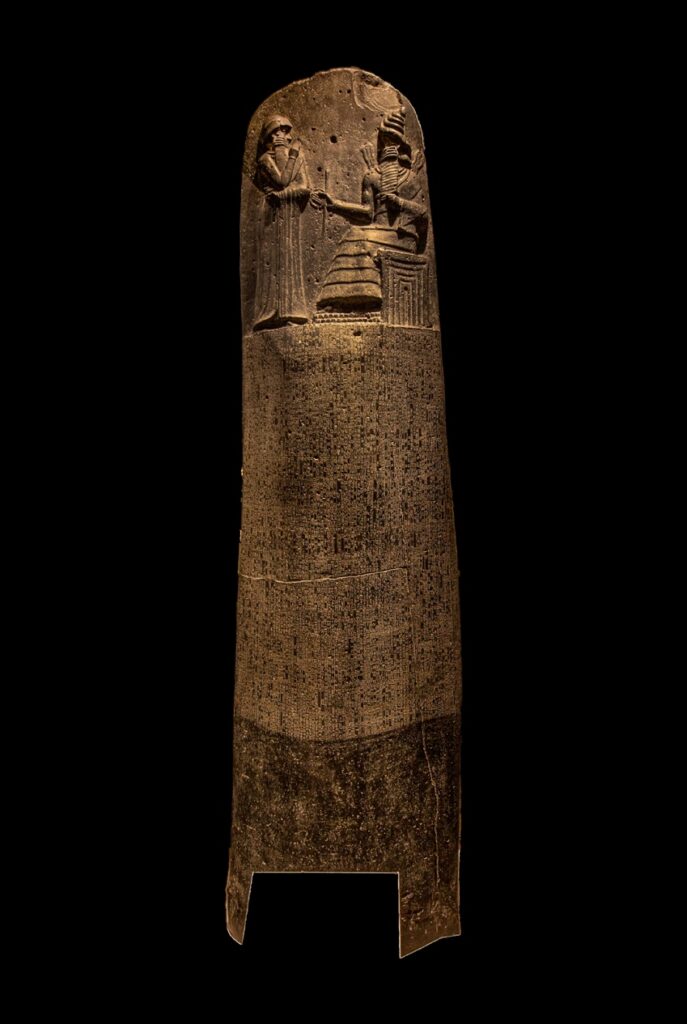

Panel: The Hammurabi Law Stele

The Code of Hammurabi is among the earliest and most important law collections from the ancient world. Written in Akkadian around 1750 BC, it contains some three hundred laws, many following the principle of “an eye for an eye.” Many copies of the code are known to have existed. The most important preserved example is in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a 7.4 foot (2.25 meter) black basalt stele excavated at Susa (Iran) in 1901. Casts of it are on display in several museums, law schools, and political institutions across the world.

Object: Hammurabi’s Law Stele

Plaster cast

Early twentieth century AD

YPM BC 038053

Original in the Louvre Museum, Sb 8

SECTION 5: SCIENCE AND SCHOLARSHIP

Once they had acquired the fundamentals of the scribal arts, many educated Mesopotamians pursued scholarly and scientific interests, from philology and grammar to mathematics, medicine, and the “futurological” study of omens. In the first millennium BC, Babylonian astronomy reached impressive levels of sophistication.

The so-called Astronomical Diaries and related works, composed uninterruptedly between the eighth and first centuries BC, record the movements of the heavenly bodies in the night sky. Other texts engage in advanced types of computational, predictive astronomy.

Important innovations during the Persian period were the zodiac and personal horoscopes, both still in use today. The division of the hour into sixty minutes of the circle into three-hundred-sixty degrees, and the naming of many heavenly bodies and constellations, from Venus and Mars to Cancer and Taurus, can also be traced back to the Babylonians.

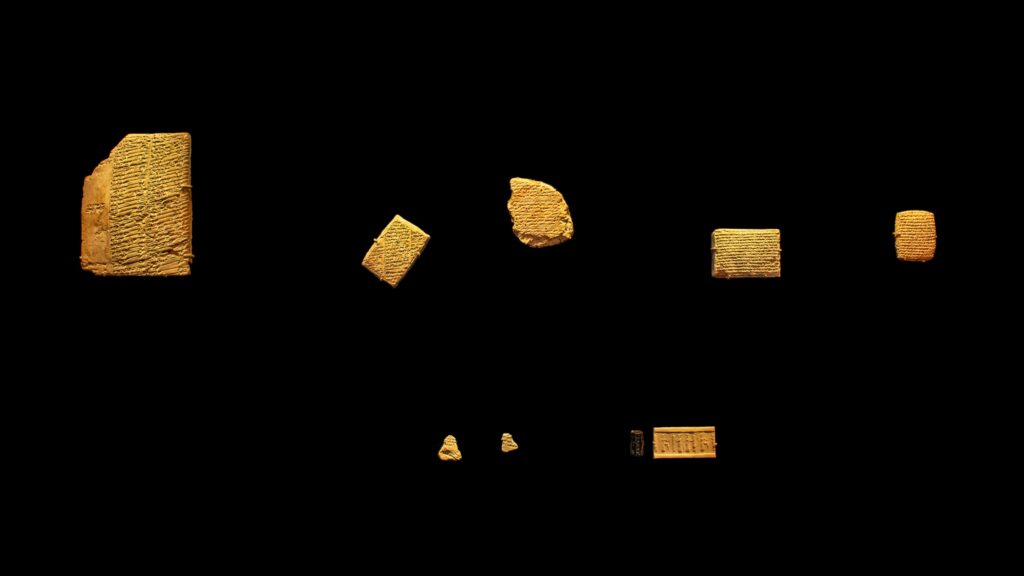

Panel: Becoming a Scribe

Exercise tablets, often written in a clumsy, inexperienced hand, put us in close contact with the students who attended Mesopotamian “schools.” Even though not every child had to memorize hundreds of signs and thousands of lines of text, literacy was probably fairly widespread, at least in the cities.

Object 1: Writing Syllables

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 012526

NBC 9560

Clay

Probably Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 018959

YBC 4895

Object 3: Satire about a Father and His Mischievous Son

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Possibly from Larsa

YPM BC 018281

YBC 4216

Object 4: Lenticular School Tablet Listing Oxen of Various Ages

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 021351

YBC 7286

Object 5: Economic Record Dealing with Cattle of Various Ages

Clay

Ur III period, third year of the reign of Shu-Suen (c. 2033 BC)

Drehem

YPM BC 016363

YBC 1622

Object 6: A Word List in Pocket Size

Clay

Kassite period (c. 1590–1155 BC)

YPM BC 013875

NBC 10915

Object 7: School Tablet with a Dedication to the God of Writing

Clay

Late Babylonian period (second half of the first millennium BC)

Babylon or Borsippa

YPM BC 002842

EAH 197

Above

Assyrian Scribes Writing Cunei orm on a Writing Board and Aramaic on a Leather Scroll

Neo-Assyrian period, reign of Sennacherib (704–681 BC)

British Museum

BM WA 124955

Panel: Measuring Space, Tracking Time

Mathematics and geometry were important elements of Mesopotamian culture, diligently studied by scribal students and applied to engineering projects, calendrical calculations, and other purposes. By the mid first millennium BC, mathematical astronomy was able to achieve remarkably accurate predictions of planetary movements and eclipses.

Object 5: Drawing the Constellations

Clay

Hellenistic period

(January 4, 214 BC)

Uruk

YPM BC 001864

MLC 1866

Object 6: Description of the Constellations and the Topography of Uruk

Clay

Seleucid period or early Parthian period (c. 300–100 BC)

Uruk

YPM BC 00188

MLC 1884

Object 7: Seal Bezel with Scorpion (Scorpio)

Carnelian

Hellenistic to Sasanian periods (c. 331–600 BC)

YPM BC 038127

NBC 12392

Object 8: Seal Bezel with Goat-fish (Capricorn)

Carnelian

Hellenistic Roman period (c. 100 BC – AD 100)

YPM BC 038128

NCBS 1070

Object 9: Seal Bezel with Scales (Libra)

Carnelian

Hellenistic Roman period (c. 100 BC – AD 100)

YPM BC 038129

NCBS 1071

Object 10: Seal Bezel with Crab (Cancer)

Carnelian

Hellenistic to Sasanian periods

(c. 331–600 BC)

YPM BC 038049

Object 11: Approximation of a Non-right Triangle’s Area

Clay

Old Babylonian period (1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 022691

YBC 8633

Object 12: A Date List with Year Names

Clay

Old Babylonian period (1712 BC or later)

Babylonia

YPM BC 016768

YBC 2140

Object 13: List of Months Suitable for Healing Rituals

Clay

Late Babylonian period (second half of the first millennium BC)

YPM BC 023831

YBC 9833

Object 14: Cylinder Seal Displaying the Divine Sun, the Moon, and the Pleiades

Chalcedony

With rolled out impression on polymer

Neo-Assyrian period (934–612 BC)

YPM BC 038114

NBC 12330

Object 15: A Normal Star Almanac

Clay

Hellenistic period (179 BC)

Uruk

YPM BC 001883

MLC 1885

Object 16: Calculating the Velocity of the Moon

Clay

Hellenistic period (331–141 BC)

Uruk or Babylon

YPM BC 001878

MLC 1880

Panel: Predicting the Future

Ancient Mesopotamians believed that the gods sent signs to help them cope with the future.

Such divine signs could be found in the movements of celestial bodies, the grooves on the liver and other organs of a sacrificial lamb, the wrinkles of a man’s forehead, and in the behavior of wild and domestic animals.

Object 1: Omens Derived from a Sheep’s Colon

Clay

Late Babylonian period, May 4, 213

Uruk

YPM BC 001872

MLC 1874

Object 2: Drawing of the Entrails of a Sacrificial Sheep

Clay

Probably Old Babylonian or Middle Babylonian period (second millennium BC)

YPM BC 016795

YBC 2167

Object 3: Liver Model Inscribed with an Omen Related to King Sin-iddinam of Larsa

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

Possibly from Larsa

YPM BC 023830

YBC 9832

Object 4: Horoscope of Aristocrates

Clay

Hellenistic period, 235 BC or later

Uruk

YPM BC 002136

MLC 2190

Object 5: List of Months Auspicious or Various Activities, with Commentary

Clay

Late Babylonian period (second half of the first millennium BC)

Possibly from Uruk

YPM BC 002575

MLC 2627

Panel: Healing

Along with their Egyptian colleagues, Mesopotamian physicians produced the earliest detailed medical texts ever written. Babylonian and Assyrian doctors identified many physical illnesses and psychological disorders. For treatments they used hundreds of plants and other substances, administered to patients to eat, or as potions, ointments, and suppositories, and through fumigation.

Top

Object: Commentary on a Text about Fumigations against Epilepsy

Clay

Persian period (539–331 BC)

Nippur or Uruk

YPM BC 001861

MLC 1863

Above

Object: Healing Scene

Neo-Assyrian period (934–612 BC)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, L.1994.88

Bottom left

Object: Incantations against the Tooth Worm and Scorpion Bites

Clay

Old Babylonian period (c. 1900–1600 BC)

YPM BC 018658

YBC 4593

Bottom right

Object: A Catalogue of Medical Treatises

Clay, four fragments from the Yale Babylonian Collection with a fragment from the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, upper left Neo-Assyrian period (eighth or seventh century BC)

Assur

YPM BC 021187, YPM BC 021190,

YPM BC 021203, YPM BC 021210

YBC 7123, YBC 7126, YBC 7139, YBC 7146

On loan from the Oriental Institute Museum

OIM A 7821

SECTION 6: YALE BABYLONIAN COLLECTION

The Yale Babylonian Collection houses more than 40,000 cuneiform texts, seals, and other artifacts. The Collection’s holdings of tablets and other inscribed objects are among the most important in the world. Among the highlights—many on display here—are an early manuscript of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s oldest cookbooks, and exquisitely carved seals.

From its founding in 1911, the Yale Babylonian Collection has been a center for research by students and faculty at Yale University, and for scholars from all over the world. It aims to preserve, publish, and make available for everyone the artifacts it houses.

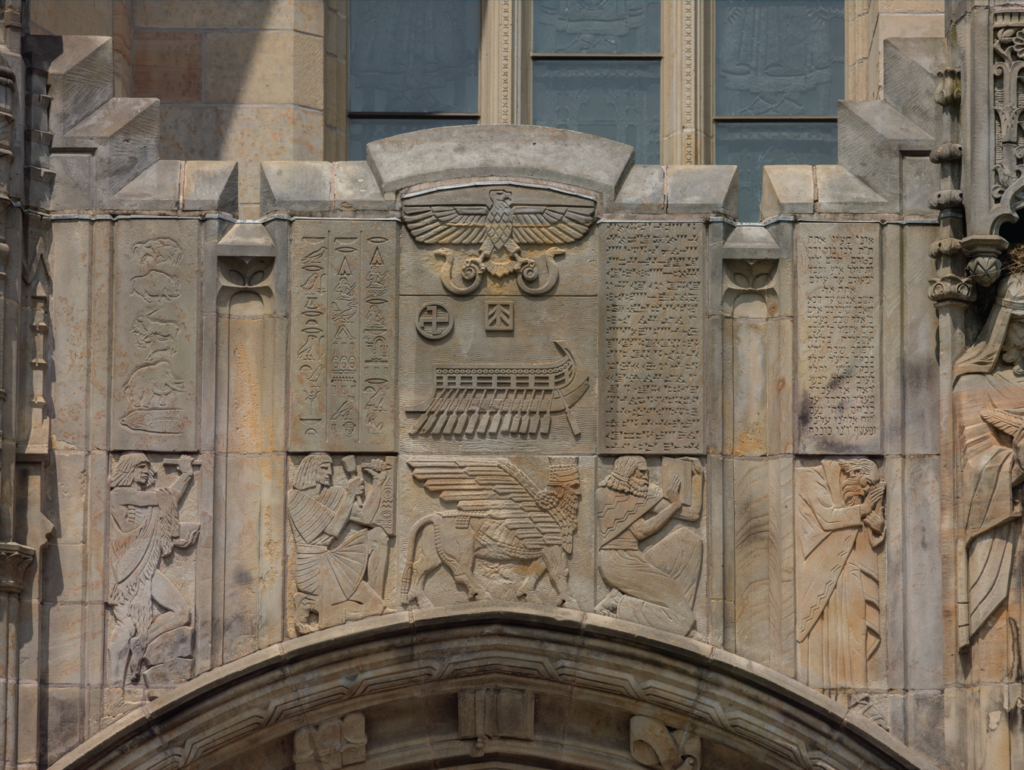

Panel: The Babylonian Collection in Sterling Memorial Library

The Yale Babylonian Collection Found its permanent home as the very first occupant of Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library, completed in 1930, in a custom-designed suite. The floor of the room intended for the collection materials was rein forced to hold their significant weight. Windows were adorned with painted and stained glass insets with iconic Assyrian and Babylonian motifs. A frieze above the library’s entrance includes an Assyrian scribe and a cuneiform inscription from the royal library of Assurbanipal.

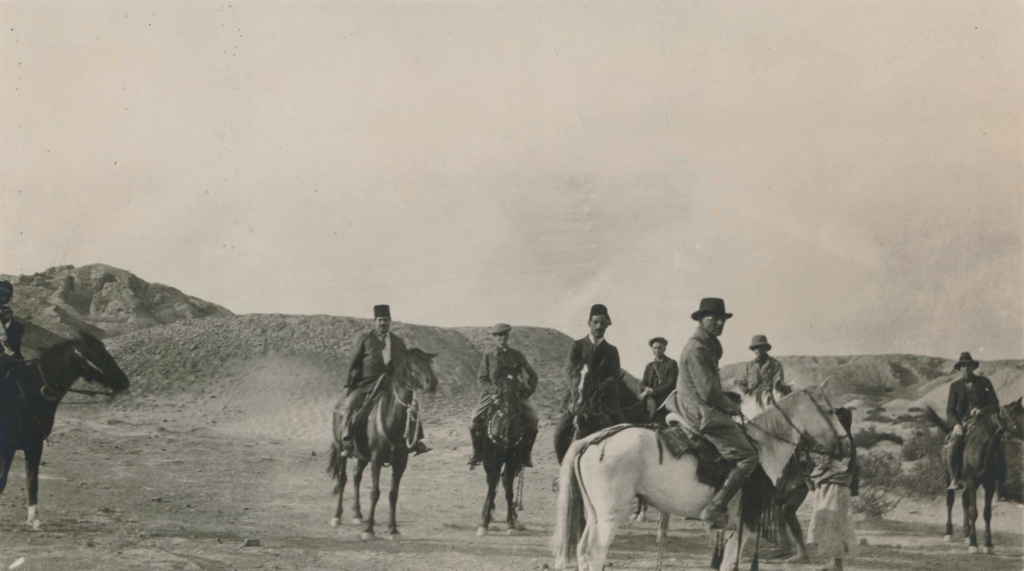

Albert T. Clay, founder of the Yale Babylonian Collection, received his doctorate in Assyriology and Semitic languages in 1894 from the University of Pennsylvania. Ambitious and energetic, he mounted expeditions to the Near East and published nineteen books. Appointed the William M. Laffan Professor of Assyriology and Babylonian Literature at Yale University in 1910, he began building a collection of inscriptions, seals, and casts with the aim of representing all periods and genres of Mesopotamian civilization.

Yale Babylonian Collection Archives

1920, Yale Babylonian Collection Archives

Cuneiform Commentaries Project and Website

Begun in 2013 in the work rooms of the Yale Babylonian Collection, Yale’s Cuneiform Commentaries Project, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, seeks to make the large corpus of Babylonian and Assyrian text commentaries available online to both the scholarly community and a wider audience. Cuneiform commentaries are the world’s oldest cohesive group of treatises that interpret literary and scholarly works. The project, co-directed by Eckart Frahm and Enrique Jiménez, collaborates with scholars and institutions worldwide.

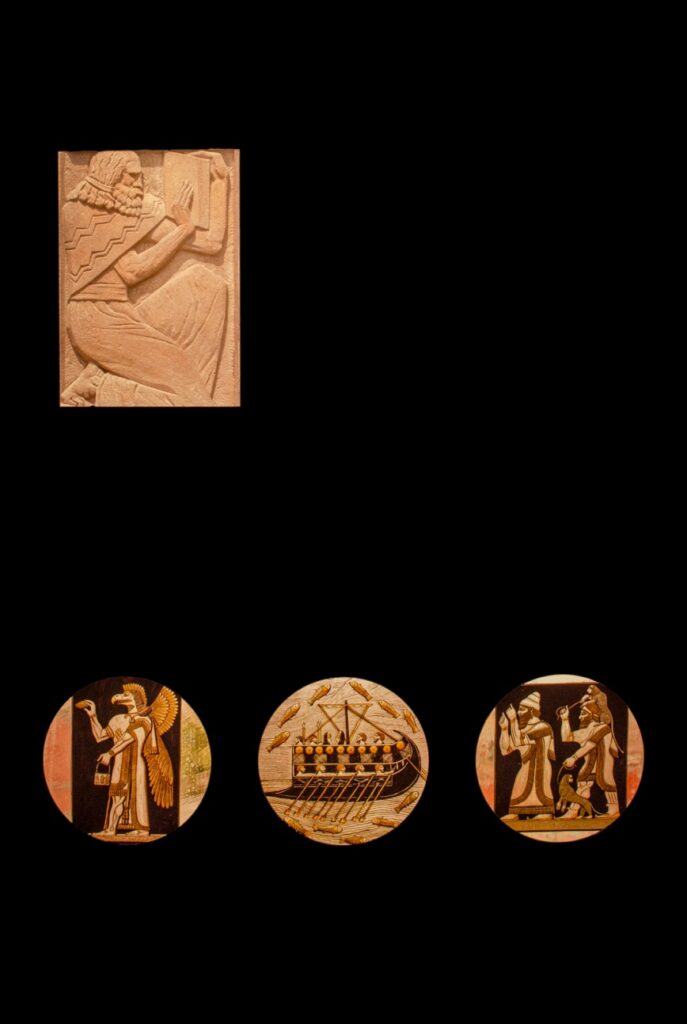

Digitizing Seals

Advanced photographic techniques and digital enhancement aid in the examination and interpretation of ancient artifacts. The flattened views of seals imaged here were captured using High Dynamic Range (HDR) photography. A stationary camera shoots sixty images around the circumference of a cylindrical seal placed in the center of a turntable. These images are then stitched together to create a flattened, two-dimensional digital roll-out. Merging different exposures enhances the carving, texture, and color of the stone.

Cylinder Seal Inscribed with a Prayer and Showing Three Deities (Jasper)

Kassite period (c. 1590–1155 BC)

YPM BC 006144

NBC 3171

Cylinder Seal Inscribed with a Prayer and Showing a Worshipper (Agate)

Kassite period (c. 1590–1155 BC)

YPM BC 006184

NBC 3211

Cylinder Seal Showing a Winged Bull and a Tree (Marble)

Kassite period (c. 1590–1155 BC)

YPM BC 037564

NCBS 667

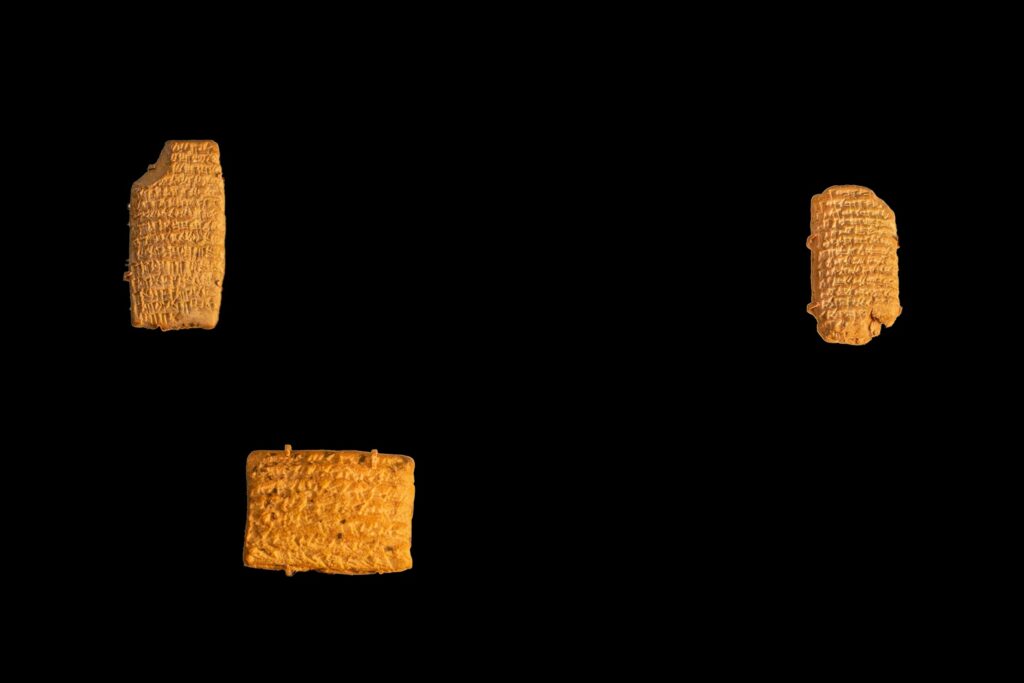

Digitizing Tablets

Because a cuneiform artifact is a three-dimensional object, reading the script with its elevations and depressions presents challenges to the reader. The alignment of light and shadow on an artifact is critical, with some angles better than others for deciphering the signs and carved scenes of seals impressed in clay. Using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), the light source can be moved around to produce high-quality dynamic images that can be manipulated and shared with scholars worldwide.

The Digitizing the Yale Babylonian Collection project, funded beginning in 2019 by the Council on Library and Information Resources, intends to digitize Yale’s cuneiform holdings in their entirety and make them available online.

Along with flatbed scanning, which will be used to document all tablets, the project will use Reflectance Transformation Imaging and High Dynamic Range Imaging to capture the detail of particularly important or damaged artifacts. The project is directed by Agnete Wisti Lassen.

Current Research

The Yale Babylonian Collection is a vibrant research facility and a center for learning for students of the ancient Near East. Despite more than a century of dedicated work, only about half of its holdings have been published. Future work will focus on conservation, digitization, and publication. This section presents some of the current research in the Collection.

Left

A Book with Hand Drawings of Two-hundred Cuneiform Letters and Documents from the Yale Babylonian Collection

Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa

Yale Oriental Series: Babylonian Texts, Volume 21

Yale University Press, 2011

Left, on book

Three Letters Regarding Business Matters of the Eanna Temple in Uruk

Clay

Neo-Babylonian period, sixth century

Uruk

YPM BC 034583, YPM BC 035705,

YPM BC 025047

NCBT 38, NCBT 1160, YBC 11253